How to Ensure China Doesn't Spoil Venezuela’s Debt Restructuring

China's oil-backed loans give it leverage to delay a comprehensive debt restructuring.

By Rachel Lyngaas

U.S. officials have framed Venezuela’s post-Maduro path as a three-step process: stabilization, recovery, then political transition, with early emphasis on restoring oil exports. But oil production alone cannot stabilize Venezuela. Decades of hyperinflation, collapsing public services, and the emigration of nearly 8 million people have left the country with acute macroeconomic and humanitarian challenges. Oil revenues are necessary—but without a credible strategy to address Venezuela’s legacy debt, they are not sufficient.

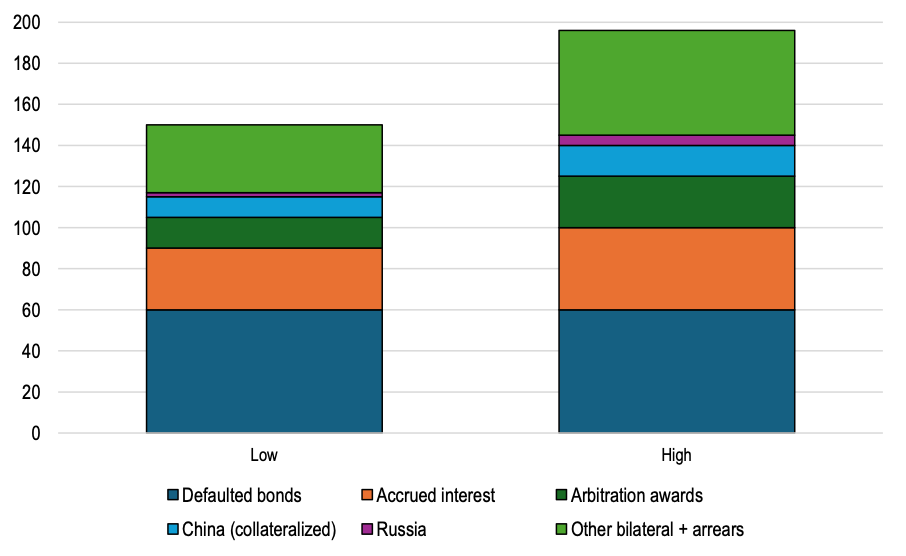

Venezuela and its state-owned oil company, PDVSA, defaulted years ago on roughly $60 billion in bonds. Its total external liabilities likely exceed $150 billion (Figure 1). Absent a credible debt restructuring, sanctions relief and higher oil output will not translate into durable stabilization or sustained investment. Instead, debt overhang and litigation risk will continue to deter the capital that Venezuela needs to rebuild its oil sector and the broader economy. In other words, investors will price in both the sheer scale of Venezuela’s unresolved debt and the risk that repayment disputes or creditor holdouts will disrupt cash flows. This means higher risk premia, limited access to long-term capital, and reluctance by international oil companies to commit fresh investment—regardless of whatever sanctions relief and additional investment guarantees are offered.

Figure 1. Venezuela’s Total External Liabilities

Low-high estimate; includes bonds, accrued interest, arbitration awards, bilateral claims, and arrears in USD billions

Sources: Reuters (Dec. 2025-Jan. 2026), IMF, CFR, public reporting on arbitration awards and Citgo-related claims. Author estimates.

The more acute risk, however, stems from China. Despite holding a relatively modest share of Venezuela’s total external debt—roughly $10-12 billion—much of China’s exposure is collateralized by oil shipments. That structure gives Beijing leverage to delay or complicate a comprehensive debt restructuring, particularly if it prefers continued oil-backed repayments to accepting a haircut.

An IMF-supported program usually serves as the anchor of sovereign debt restructurings: it combines financing and policy conditionality, establishes a debt sustainability framework, and signals to markets that appropriate reforms are underway. That, in turn, helps catalyze external financing and encourages creditor coordination. Without such a program, Venezuela will struggle to unlock broader financing, stabilize its economy, and attract the investment needed to restore oil production.

China’s Spoiler Role

China’s role as the world’s largest bilateral creditor has complicated recent sovereign debt restructurings to the detriment of its borrowers. In Zambia, it took more than two years after the November 2020 default for China to provide the financing assurances required for IMF lending. Comparable delays followed Sri Lanka’s 2022 default and Ghana’s 2022 moratorium. These episodes were driven by protracted negotiations over debt perimeter, demands for comparable treatment, and procedural delays on the Chinese side.

Such delays matter. Protracted post-default restructurings are associated with large output losses and persistently weaker investment outcomes. In addition, Chinese official lending has frequently relied on commodity-linked repayment arrangements that route export proceeds through accounts controlled by the creditor. This effectively grants Chinese lenders seniority over other claims.

In response to such challenges, the IMF has reformed its lending framework to allow programs to proceed even when official creditor assurances are delayed, which limits the ability of a single creditor to veto financing. But the IMF framework also recognizes a practical constraint: when a creditor can exert “significant influence” over the debtor’s repayment capacity, the Fund may still require that creditor’s participation.

Chinese official lending has frequently relied on commodity-linked repayment arrangements that route export proceeds through accounts controlled by the creditor. This effectively grants Chinese lenders seniority over other claims.

In oil-backed cases like Venezuela, China meets that “significant influence” threshold because collateralized oil shipments give it the ability to extract preferential repayment, particularly after the IMF program ends. As a result, unless IMF staff can credibly demonstrate that the program architecture prevents off-terms repayment, China would likely need to be part of any “sufficient set” of creditors providing assurances. This is the channel through which China could act as a spoiler, even under the IMF’s reformed approach.

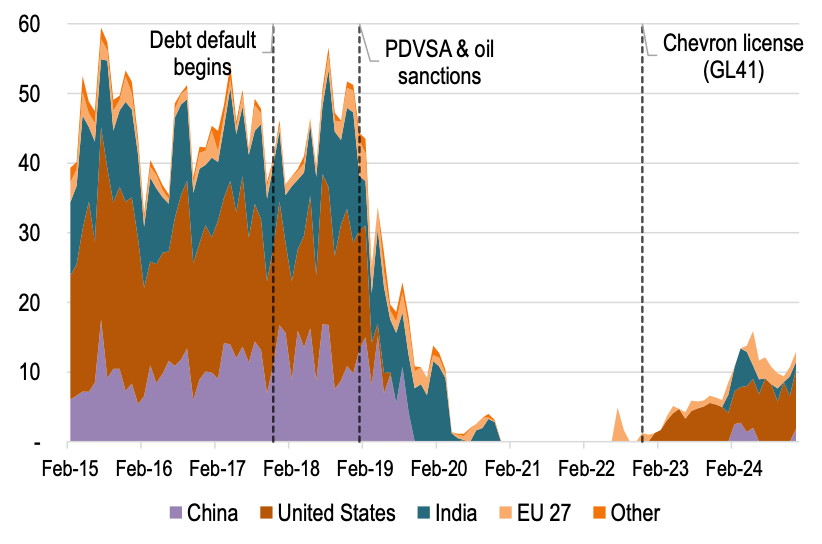

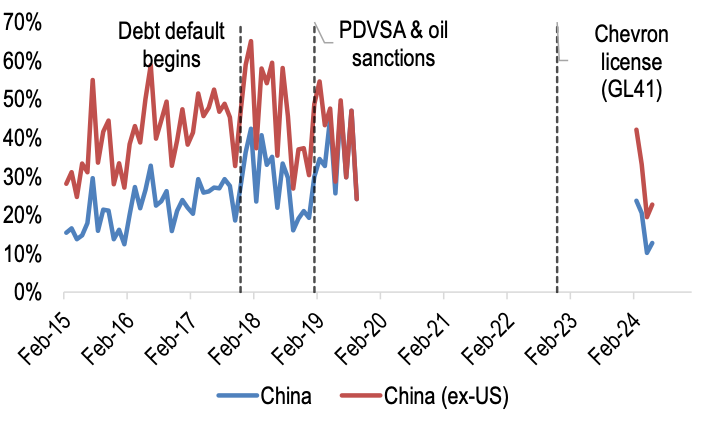

Export data illustrate how China’s role has evolved into a de facto buyer of last resort for Venezuelan oil. Following default and the imposition of PDVSA and oil sector sanctions, crude oil export volumes collapsed, and destinations narrowed sharply (Figure 2a). When U.S. purchases under Chevron’s license are excluded, China’s share of remaining exports rises markedly, underscoring its outsized role in the post-sanctions period (Figure 2b). While China’s absolute import volumes decline after sanctions, its share of Venezuela’s non-U.S. export market increases—reflecting reduced diversification.

Figure 2a. China’s share of Venezuelan crude exports

Monthly, millions of barrels

Figure 2b. China’s share of Venezuelan crude exports

Monthly, % of total and % of total ex. U.S.

Sources: Trade Data Monitor, EIA, author’s calculations.

Using U.S. Leverage

While the IMF’s engagement with Venezuela has been suspended since 2019, there are signs that its shareholders will greenlight reengagement. Once that occurs, the existing executive order requiring Venezuela’s oil proceeds to be deposited into U.S.-custody Treasury accounts could be used as a temporary transparency and control mechanism during restructuring. Under this approach, proceeds from licensed oil exports would flow through monitored accounts, allowing revenues to be tracked, audited, and safeguarded against preferential creditor repayment. Two steps would make that approach more robust.

First, the U.S. should build oil revenue controls into the licensing regime. Any U.S.-authorized Venezuelan exports should use centralized, auditable payment routing and standardized disclosure of realized prices, discounts, counterparties, and intermediaries. Washington can ban — or tightly circumscribe — advance payments, cargo-financing structures, and opaque swaps that function as off-balance-sheet repayment. Revenue controls are not a substitute for stabilization policy, and if designed poorly they could inadvertently constrain the government’s ability to fund essential imports and basic services. That is precisely why any controls should be paired with auditable payment routing and independent monitoring: to ensure that oil revenues translate into usable foreign exchange for stabilization rather than opaque creditor capture. These controls should include sunset provisions tied to completion of an IMF program or comprehensive debt restructuring.

These revenue controls can be executed largely through existing Treasury authorities. The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) already requires detailed reporting from authorized persons under Venezuela sanctions, and the Chevron license has included restrictions on payment flows. Independent monitoring adds complexity, but there is precedent in revenue transparency frameworks like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

Second, the U.S. should make China’s leverage less valuable by reducing buyer concentration and standardizing a settlement instrument. The fastest way for China to extract preferential repayment is to become the residual buyer of Venezuelan oil—or act as a gatekeeper during a transition. The United States can blunt that by encouraging early diversification of oil exports (where legally and commercially feasible) and by pushing a transparent restructuring template that offers upside without side payments (e.g., long-dated instruments plus contingent value linked to production recovery) available only to participating creditors on comparable terms. Upside participation rather than outright losses gives Beijing a face-saving channel to accept haircuts without preserving special access to the repayment stream.

This second step will require sustained diplomatic coordination. Aligning creditors around a transparent restructuring template demands engagement with bondholders, bilateral creditors, and arbitration claimants with divergent interests. Still, much of Venezuela’s bond stock is governed by New York state law and the U.S. sanctions and licensing regime is a gatekeeper for many transactions—meaning Washington has significant political influence and could convene such a coalition.

These two steps would reduce the scope for hidden repayments and would strengthen debt transparency—both essential for an IMF program anchored on credible macroeconomic parameters. They also would protect Venezuela’s immediate stabilization and recovery by helping ensure that early oil revenues translate into usable foreign exchange for essential imports, rebuild basic fiscal capacity, and support a path to recovery of production—rather than being siphoned off into opaque creditor side-payments that will deter new investment. Absent these safeguards, the United States’ three-step plan risks foundering on the same creditor coordination failures that have plagued other debt restructurings where China holds the cards.

Rachel Lyngaas is a senior policy researcher at RAND and a professor of policy analysis at the RAND School of Public Policy. She was previously Chief Sanctions Economist at the U.S. Department of the Treasury, where she built and led the Sanctions Economic Analysis Division within the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), and worked as an economist at the International Monetary Fund and in Treasury’s Office of International Affairs. She is a member of the Bologna Initiative for Sanctions Relief.

Photo: Canva